Insights

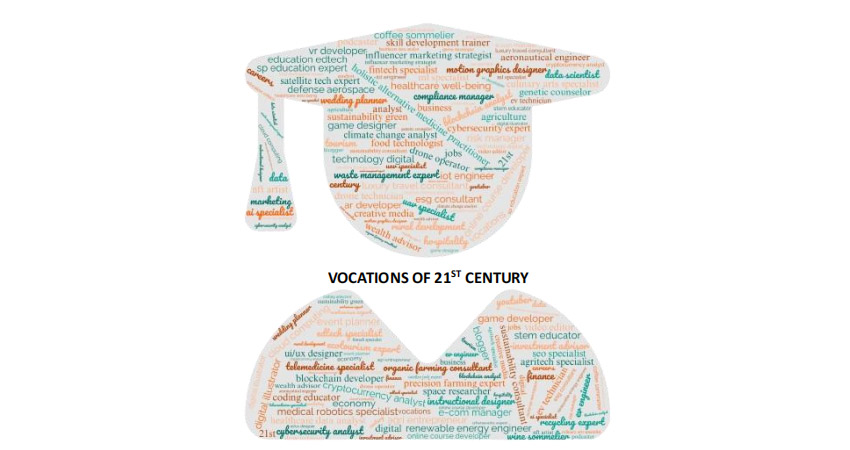

The findings raise a significant point about children skills and academic progress. While it is a good thing that the children with market jobs are proficient at generating rapid answers, it would likely be better for the long-term futures if they also did well in school and wound up with a high school degree or better.

Observations

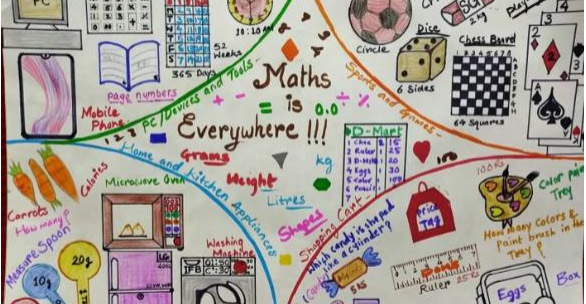

Finding a way to cross the divide between informal and formal ways of tackling math problems, then, could notably help some Indian children.

Basically, there's a gap between school skills and street skills when it comes to math in India. We need educational approaches that bridge the gap between practical and academic math skills.

The study shows how important it is to integrate practical problem-solving into the academic curriculum. This can help children better apply mathematical concepts in real-world scenarios, which can boost the overall understanding and utilisation of the math skills being taught at school.

There is a big gap in how math is taught versus how it is used in daily life. Market-working children develop impressive mental math skills because of constant exposure to calculations in their work. But these skills don’t align with formal education methods, which require a structured approach.

Meanwhile, school-going children excel in exams but may struggle with spontaneous number crunching in real-life situations.

Thus, schools could benefit from incorporating real-world problem-solving into math lessons. Bridging the gap between practical and academic math could help children develop well- rounded numerical skills regardless of their background.

Experiences

Maths curricula taught in primary school ought to provide children with the concepts and skills that they need both for their daily lives and as a foundation for learning the higher maths required to succeed in school at more advanced levels. Too often, however, formal schooling fails to achieve either of these goals. In India, in 2023, only half of the children enrolled in grades 11 and 12 (16–18 years of age) could divide a three-digit number by a single-digit number. Globally, learning outcomes remain poor despite large increases in school enrolment in many low-to-middle-income countries.

Moreover, children seem even less likely to be able to use basic arithmetic skills in everyday life. A recent study in India, for example, found that only half of the children enrolled in grades 11 and 12 could calculate how many purifying tablets to use in a large pot after they were given the number they needed for a smaller pot. Notably, 35% of the children who were able to solve an abstract division problem failed this verbal exercise.

However, many children in low-to-middle-income countries, for instance, those who work in markets, seem to routinely perform more involved calculations as part of their daily jobs. For example, a study in the 1980s of five children who worked as street vendors (mean age of 11 years) in Brazil found that these children ably and flexibly used maths in their work. These findings are in line with ethnographic studies of adults with minimal formal education who also exhibit these abilities.

Moreover, decades of research, mostly in Western countries, have shown that children can adeptly combine small sets to create exact larger numbers well before schooling begins and that their facility of learning maths in primary school is associated with their sensitivity to approximate number in later years of schooling. A prominent theory in cognitive psychology suggests that learning maths in meaningful real-world contexts can complement maths learnt in the classroom and provide children with more generalizable and flexible arithmetic skills. By learning and practising maths through relevant contexts, children may be better equipped to acquire the flexible cognitive skills they need to transfer maths knowledge across domains. Under this hypothesis, children who work in markets might be expected to more easily learn the abstract maths taught in school. However, just as children who master abstract maths skills in school may fail to apply them to concrete problems, schools may fail to help children who adeptly use maths concepts in concrete situations in their daily lives to develop more abstract, generalizable skills. In the absence of such help, such skills may not automatically transfer across domains in either direction.

The marked gap between the strong performance of the working children on real and hypothetical market transactions and their weak performance on the written exercises presented in school is unlikely to be explained by the difficulty of the underlying arithmetic calculations. If anything, the operations required by the market transactions were more difficult than those of the written arithmetic problems on the ASER, as the market transactions involved several operations.

Working children do less well on abstract maths questions because they resort to poorly mastered algorithms taught in school. Conversely, school children do poorly in applied problems because they do not know any strategies other than those taught in school and they have not mastered those strategies sufficiently well to solve these more involved problems. It is possible, however, that the children’s performance was impaired by stress, stereotype threat or weak incentives to perform accurately.

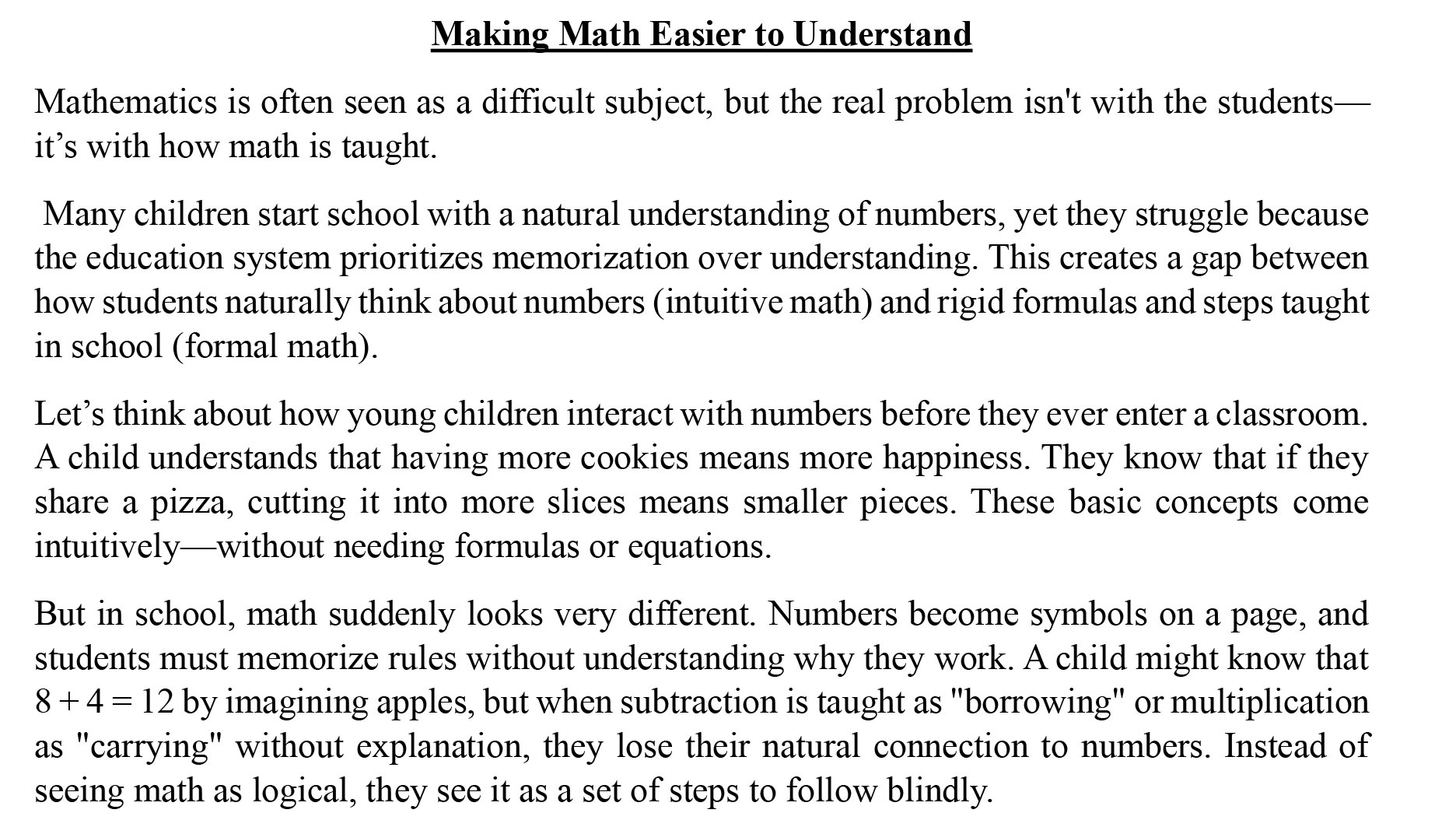

The low performance of working children and school children in primary school maths problems also calls for changes in how maths is introduced to children, in particular to better synergize intuitive knowledge and training in symbolic maths.

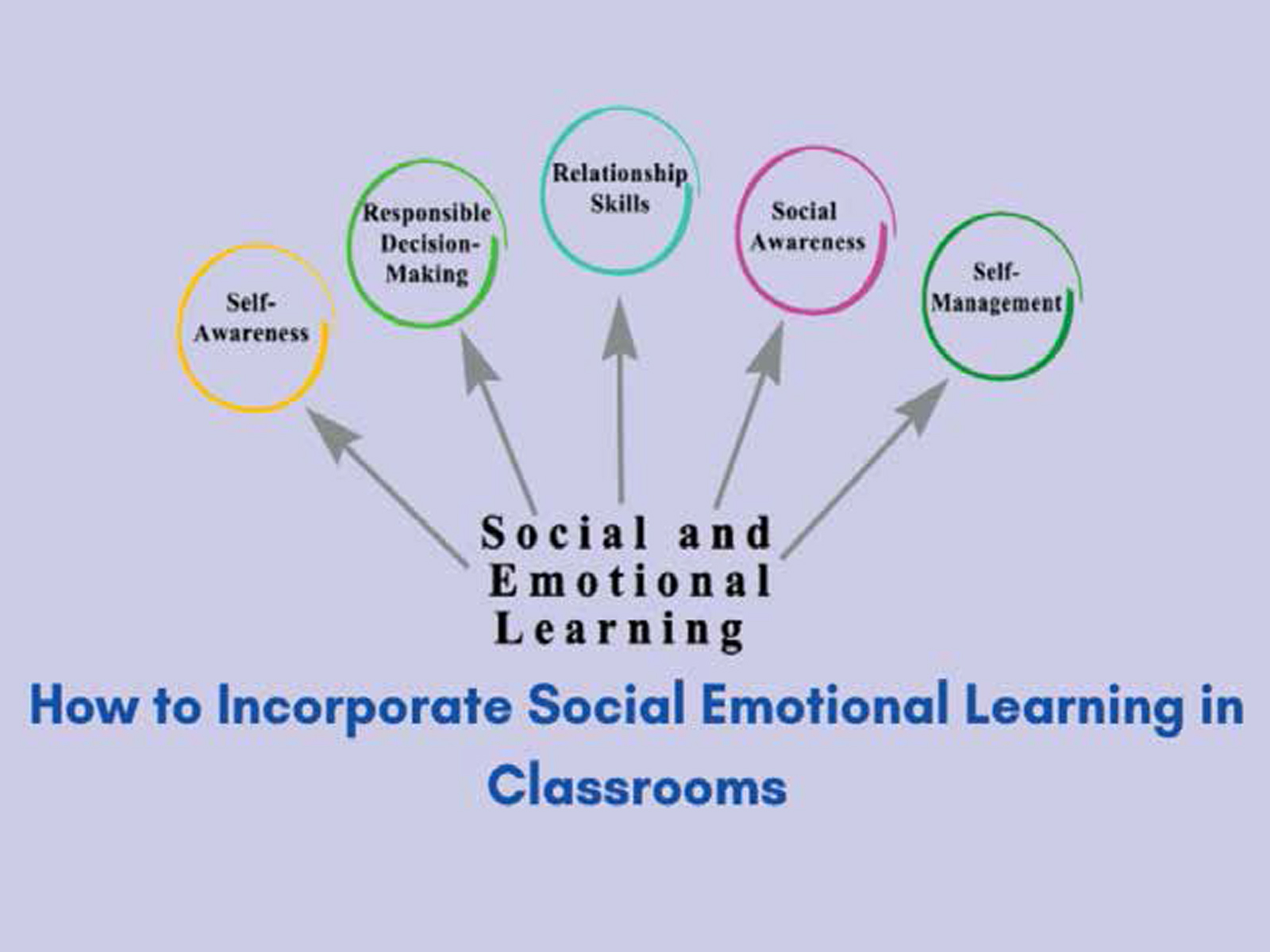

These findings call for a maths pedagogy that explicitly addresses these translational challenges through curricula that connect abstract maths symbols and concepts to intuitively meaningful contexts and problems. Consistent with that call, a RCT found that introducing financial education to public high school children in Brazil was effective not only in improving financial literacy but also in reducing school failure rates, with qualitative interviews suggesting that children felt more engaged with maths presented in familiar contexts.

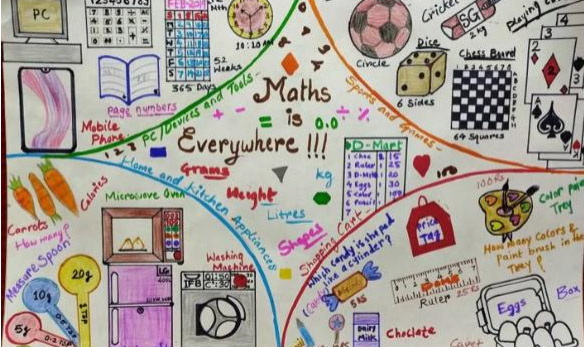

Math in the Marketplace

Children working in Indian markets demonstrated impressive mental arithmetic abilities. They could rapidly calculate costs, provide correct change, and solve multi-step problems efficiently. When tested in hypothetical market-based scenarios, they continued to perform well, indicating their skills were not merely rote memorization.

These findings highlight the importance of educational curricula that bridge the gap between intuitive and formal mathematics

Child vendors can mentally calculate complex market transactions in seconds but struggle with simpler abstract maths taught in schools, while their school-going peers excel at academic maths but fail at basic real-world calculations.

Conclusion

- Market working children in India excel practical math but struggle academically.

- School going children excel academically but struggle practical mathematical skills

- Study suggests integrating practical problem solving into academic curricula

Plan of Action

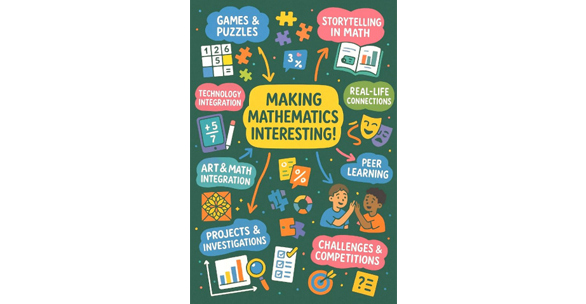

- Practical life examples should be discussed and applied in the classrooms to teach a concept.

- More Mental Math Application-Many children helping in family businesses develop quick calculation skills

- Flexible problem solving- Instead of rigid school methods, children should be taught to use shortcuts, approximation, and intuition.

- Money handling and accounting- Understanding profit margins, discounts, and interest rates and their applications should be focussed upon.

- Applied Mathematics and Pure Mathematics should be taught in an integrated manner.

- Projects and surveys related to real life Mathematical Problem Solving Skills should be given to children.

Mrs. Aakshi Bajaj

TGT Mathematics

Modern School Vasant Vihar

New Delhi 110057

Akshi has been working in the above mentioned esteemed school since 2011. Passionate in teaching of Mathematics. Studied B.A(Hons) Mathematics from Jesus and Mary college, Delhi University, then M.A in Pure Mathematics from St. Stephen's College , Delhi University, B.Ed from KIIT College of Education, MDU.